Article originally published by NeuroNews

‘Upstream’ causes of health inequities related to stroke—such as structural racism and conditions of the places where people live, learn, work and play—have not been studied well, according to a recent American Heart Association (AHA) scientific statement. The statement, now published in the journal Stroke, reviews the most recent research on racial and ethnic inequities in stroke care and outcomes, as well as identifying knowledge gaps and areas for future research.

“There are enormous inequities in stroke care, which lead to significant gaps in functional outcomes after stroke for people from historically disenfranchised racial and ethnic groups, including Black, Hispanic and Indigenous peoples,” said Amytis Towfighi (Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, Los Angeles, USA), chair of the scientific statement’s writing group. “While research has historically focused on describing these inequities, it is critical to develop and test interventions to address them.”

Stroke disproportionately affects historically disenfranchised communities, yet the disproportionate risk among these communities is “not well understood”, the statement details. Historically disenfranchised populations are also “vastly underrepresented” in stroke clinical trials—which contributes to the lack of understanding and reduces the generalisability of research findings, in turn exacerbating inequities that lead to poorer outcomes.

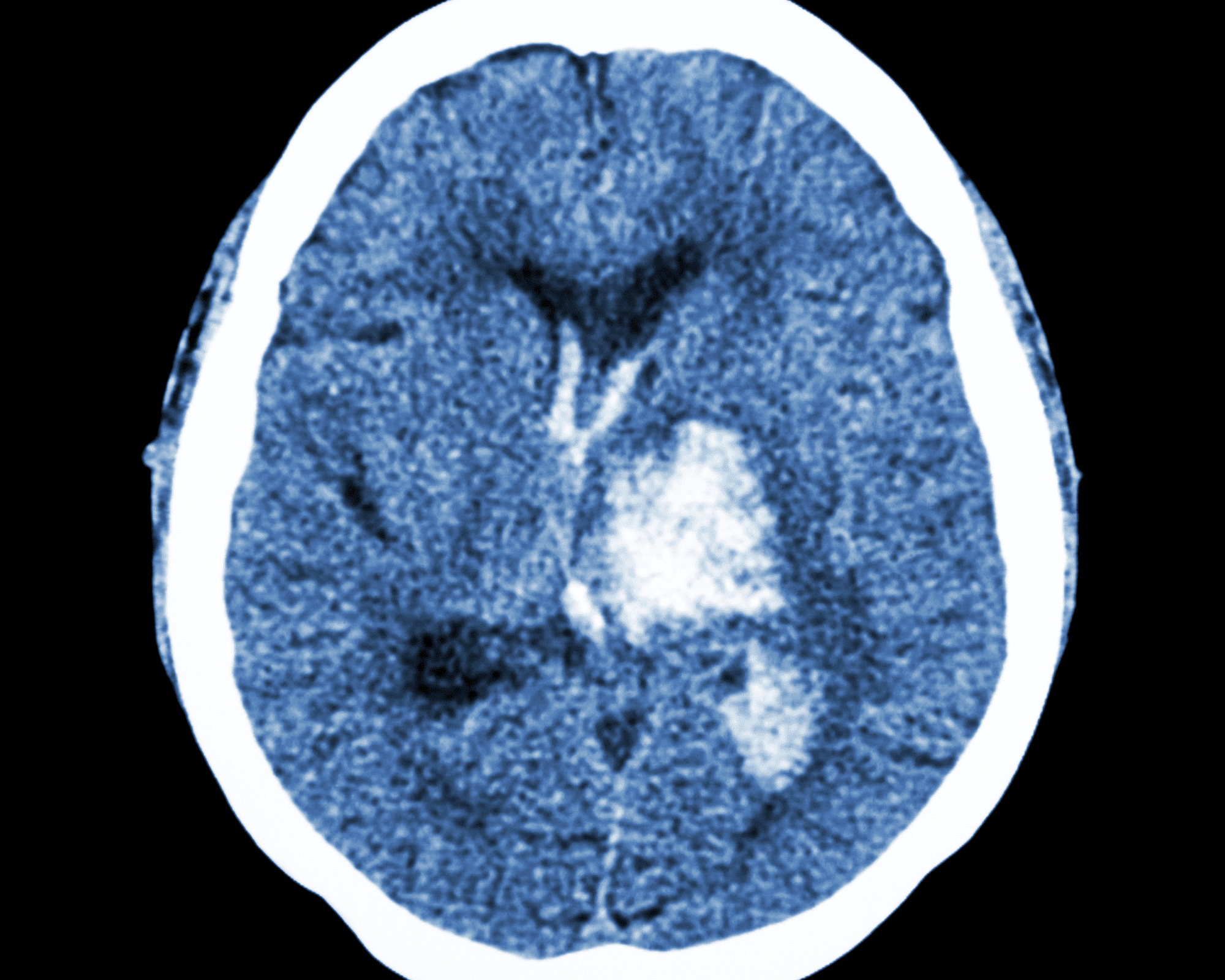

To reduce the lasting effects of ischaemic stroke caused by a blood clot, medication to dissolve the clot (intravenous thrombolysis [IVT]) should be administered within three hours, or up to four-and-a-half hours in some people, after symptoms begin. Mechanical removal of the clot (endovascular therapy [EVT]) may be safe for some people up to 24 hours after stroke symptoms start as well. However, not all people experiencing a stroke have rapid access to these treatments, the statement adds.

“Time is vital for stroke treatment; however, people from historically disenfranchised populations are less likely to get to an emergency room within the time window for acute intervention,” Towfighi continued. “Although Black people are more likely to participate in a post-stroke rehabilitation programme, research indicates they are more likely to have poor functional outcomes. In addition, there are persistent racial and ethnic inequities in post-stroke risk factor control, and studies specifically addressing these inequities have not found the optimal method to mitigate the disparities.”

Most studies reviewed by the statement addressed individual, patient-level factors, such as health literacy, stroke preparedness, medication adherence and lifestyle behaviours. Few addressed upstream factors, such as structural racism—including racist policies that led to residential segregation—or environmental factors, often referred to as social determinants of health, such as community deprivation; economic stability; health insurance; housing; neighbourhood walkability and safety; the availability and affordability of healthy food options; education quality; and employment, the statement notes.

“Combating the effects of systemic racism will involve upstream interventions, including policy changes, place-based interventions and engaging with the healthcare systems that serve predominantly historically disenfranchised populations and the communities they serve, understanding the barriers, and collaboratively developing solutions to address barriers,” it also details.

Previous studies have indicated that “careful attention” to stroke preparedness among patients, caregivers and emergency medical personnel may reduce inequities in getting people suspected of having a stroke to the emergency room quickly and prompt treatment. However, according to the statement, there has not been sufficient attention on reducing inequities in rehabilitation, recovery and social reintegration, which includes information like assessing the impact of neighbourhood/city-level interventions like improved sidewalks, and access to physical, occupational and speech therapy.

The statement acknowledges that racial and ethnic identity are complex, and race is a social construct, rather than a biological one. In addition, research has often oversimplified and/or misclassified race, as per the statement. For example, in the USA, ethnicity has been long categorised as Hispanic or non-Hispanic, which “arbitrarily combines the myriad of ethnicities into only two categories”. Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders are frequently grouped together with Asian Americans, ignoring the disproportionate impact of stroke within Indigenous communities.

“In our review, we used the race and ethnicity categories typically supported by governmental research funding agencies that drive how data are collected,” said Bernadette Boden-Albala (University of California Irvine, Irvine, USA), vice chair of the statement writing group. “However, we are cognisant that these categories are inadequate to describe the nuances of lived experiences and to fully illuminate inequities that are entrenched in societal structures, including healthcare.”

Further research is needed across the stroke continuum of care to tackle racial and ethnic inequities in stroke care, and improve outcomes, the statement also notes.

“It is critical for historically disenfranchised communities to participate in research so that researchers may collaborate in addressing the communities’ needs and concerns,” Boden-Albala added. “Opportunities include working with community stakeholder groups and community organisations to advocate for partnerships with hospitals, academic medical centres, local colleges and universities; or joining community advisory boards and volunteering with the American Heart Association.”

“Healthcare professionals will need to think outside the ‘stroke box’—sustainable, effective interventions to address inequities will likely require collaboration with patients, their communities, policymakers, and other sectors,” Towfighi concluded.